Tackling plastic pollution at the source through ecofriendly menstruation products

Single-used pad photographed under water in Hundvåg in Byfjorden, Stavanger. (Photo: Rudolf Svensen).

Authors: Diya Chakravorty and Vilde Kloster Snekkevik, Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA)

It is estimated that over 12 billion disposable menstrual hygiene products are utilized annually (Barth, 2021). The production of single-use menstrual products emits around 245,000 tonnes of CO₂ annually. They contain plastics and associated chemicals (Cabrera & Garcia, 2019) and after use most of them end up in landfills where they can take up to 500 years to decompose (UNEP, 2021).

Improper disposal is a global challenge

Improper disposal of these products in the toilet result in pollution of rivers and beaches (WoMena, 2019). The improper disposal of menstrual waste represents a global challenge, significantly contributing to plastic pollution.

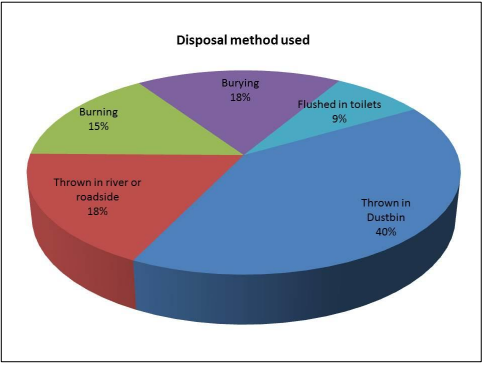

In India, a substantial portion of the 113,000 annual tons of menstrual waste produced annually faces inadequate disposal methods. 15% is burned, 18% thrown in rivers or streets, and 9% flushed down toilets. Similar issues are observed in the United Kingdom, where coastal studies uncovered alarming numbers of sanitary products (Bhor & Ponkshe, 2018).

Sanitary waste disposal methods followed in India. (Source: Bhor & Ponkshe, 2018)

This is also seen in other European countries with menstruation products ranking as the fifth-largest contributors to plastic pollution on European coastlines (Parliament, 2021). The consequences extend beyond environmental pollution, causing plumbing and mechanical problems in sewage systems (Ashley et al., 2005; Weir, 2015).

Environmental and health impact

Single-use sanitary products are not only an environmental issue, but they also have potential health impacts. The vagina can effectively transfer and transport toxic substances, and concerns have been raised regarding the potential absorption of toxic chemicals through tampons, potentially introducing toxic chemicals such as cadmium, lead, and mercury (Upson et al., 2022).

Exposure to these metals is a public health concern and can increase the risk of kidney, cardiovascular, and inflammatory diseases among users (Singh et al., 2019). Tampons and pads also contain chemicals used for bleaching, which may have a potential adverse impact on both reproduction and development (Scranton, 2013).

Photo by Antoine GIRET

Available alternatives

Environmentally friendly menstruation options are available, such as menstrual cups, menstrual underwear, and cloth pads. These alternatives are better for personal health and the environment and will pay off financially for both private users and society in the long run.

While reusable products are growing in popularity, the lack of information, awareness and accessibility often keep them on the fringe (Hait & Powers, 2019). Assessments of the environmental impact of menstrual products have shown that reusable menstrual products, such as menstruation cups, exhibit significantly lower environmental footprints compared to single-used alternatives (UNEP, 2021).

This is due to the durability of reusable options. However, reusable products produced using cotton could be problematic due to the resource-intensive production process. In some regions, access to water could make it difficult to clean re-usable pads.

EU Ecolabel criteria

In recognizing the pressing environmental concerns associated with disposable menstrual hygiene products, the European Commission has adopted new EU Ecolabel criteria for absorbent hygiene products and reusable menstrual cups, with the aim to provide environmentally friendly alternatives, foster sustainable consumer behaviour and reduce single-use plastics.

It focuses on ensuring high product quality and environmental performance throughout the product lifecycle and to decrease the negative environmental impact of hygiene products. This initiative aligns with the growing awareness of the impact of single-use menstrual products, emphasizing the need for a shift towards more sustainable options to mitigate both environmental and health-related challenges.

A journey through time – the history of menstruation products

Throughout history, menstruation has been a natural and recurring aspect of women’s lives. In ancient Greece, menstruators mimicked modern day tampons by utilizing wood with lint and sea sponges (Ahmed, 2022). Tampons produced today still resemble those from the 1930s, typically made from cotton or paper and attached with a string.

The era of disposable menstrual products began when the first pads were sold in a drugstore in 1921. Disposables increased in appeal as more women entered the labour force. It offered features such as easy availability, discretion, and efficiency (Borunda, 2019).

The design of menstrual products has undergone significant evolution over the decades. Self-adhesive strips succeeded sanitary belts in the 1970s and subsequently, plastic tampon applicators. The 1990s brought about the use of absorbent gels, enabling a reduction in the size of sanitary pads.

Currently, single-use pads are typically made of synthetic fibre, cotton, plastic, adhesive, and super-absorbent polymers like those in nappies. Tampons share a similar composition, with the addition of an applicator, usually made of plastic or cardboard, to facilitate insertion for some products (Notman, 2021).

Photo by Natracare

Existing research on alternatives

Environmentally friendly alternatives may initially have a discouraging price for some upon the first purchase, but over time, they prove to be the most cost-effective option because they can be used multiple times (van Eijk et al. 2021).

These are products that have been on the market for a long time and have many satisfied users. However, they still receive too little attention. Usage often depends on factors like availability, cultural norms, personal preference, disabilities, knowledge of their use, and affordability (UNICEF, 2019).

Until now, most studies on the use of alternative products have primarily been conducted in countries of Global South (Elledge et al., 2018; Foster & Montgomery, 2021). In these countries, the response has generally been positive, despite a lack of sanitary conditions and privacy. Dissatisfaction with the products is primarily attributed to lack of knowledge, training, and guidance on the correct use of the products (Pednekar et al., 2022).

As an example, studies have shown that once behavioural barriers are overcome, there is a high acceptance of using a menstrual cup. There is no significant health risk associated with the use of menstrual cups, and they require less water and maintenance compared to reusable pads.

The risk of infection and allergies compared to single-use products is lower and menstrual cups were found to make it easier to maintain a healthy vaginal pH and microbiome.

Photo by Oana Cristina

Adoption of reusable menstrual products

To initiate the use of alternative products, comprehensive training, sufficient knowledge and information about usage, as well as facilitation for easier use, are required. Providing information about the environmental and heath challenges posed by disposable products can also motivate girls to opt for more environmentally friendly alternatives.

Both disposable and alternative menstrual products face stigma, with alternative menstrual products differing from disposable ones by requiring a more “hands–on” approach, involving insertion, washing and reuse (Pednekar et al., 2022).

The adoption of reusable menstrual products is influenced by hygiene maintenance, water accessibility, and concerns about leakage. Which menstrual products other girls use, and in particular mothers, is important.

Young girls are often introduced to disposable products first, as these are the best-known products used by their mothers, sisters and friends. Once a decision on the type of menstrual product is made, it can be more challenging to switch to new products.

It is vital to provide good information and knowledge on reusable menstrual products to girls at an early age. Schools and health stations are therefore important platforms to provide information and guidance on more environmentally sustainable menstrual products.

Summary

The global female hygiene products market is predicted to continue growing, especially in North America and Asia Pacific (ARC, 2022).

As the demand and market for menstrual products continues to rise, it becomes critical to consider the impact of single-use products on plastic pollution, the environment, and human health.

Reusable alternatives such as menstrual cups, cloth, and reusable pads offer more sustainable options, reducing environmental and human health impact while promoting innovative reusable menstrual product solutions.

However, as their adoption faces challenges related to knowledge, awareness, accessibility and cultural norms, comprehensive information and training is required to overcome these barriers.

With the newly introduced EU criteria for hygiene products and reusable alternatives, we hope that the momentum will be used to promote sustainable consumer behaviour and reduce single-use plastics.

Read the full report (in Norwegian) here.

Edited by: Jannike Falk-Andersson and Caroline Enge

References

Ahmed, S. (2022). Periods through history: A Menstrual Timeline. Ruth. https://getruth.ca/blogs/ruth-blog/periods-through-history-a-menstrual-timeline

ARC. (2022). Feminine Hygiene Products Market Analysis – Global Industry Size, Share, Trends and Forecast 2022 – 2030. Acumen Research and Consulting. https://www.acumenresearchandconsulting.com/feminine-hygiene-products-market

Ashley, R., Blackwood, D., Souter, N., Hendry, S., Moir, J., Dunkerley, J., Davies, J., Butler, D., Cook, A. J., & Conlin, J. (2005). Sustainable disposal of domestic sanitary waste. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 131(2), 206-215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2005)131:2(206)

Barth, T. (2021). Making Menstruation Products Eco Friendly. Plastic Oceans International. https://plasticoceans.org/making-menstruation-products-eco-friendly/

Bhor, G., & Ponkshe, S. (2018). A Decentralized and Sustainable Solution to the Problems of Dumping Menstrual Waste into Landfills and Related Health Hazards in India. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(3), 334. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n3p334

Bobel, C., Winkler, I. T., Fahs, B., Katie, ·, Hasson, A., Arveda, E., · K., & Roberts, T.-A. (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7

Borunda, A. (2019). How tampons and pads became so unsustainable. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/how-tampons-pads-became-unsustainable-story-of-plastic

Cabrera, A., & Garcia, R. (2019). The environmental & economic costs of single-use menstrual products, baby nappies & wet wipes. https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bffp_single_use_menstrual_products_baby_nappies_and_wet_wipes.pdf

Elledge, M., Muralidharan, A., Parker, A., Ravndal, K. T., Siddiqui, M., Toolaram, A. P., & Woodward, K. (2018). Menstrual Hygiene Management and Waste Disposal in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112562

Foster, J., & Montgomery, P. (2021). A study of environmentally friendly menstrual absorbents in the context of Social Change for adolescent girls in Low- and Middle-Income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189766

Notman, N. (2021). Single-use plastic in period products. https://edu.rsc.org/feature/single-use-plastic-in-period-products/4013167.article

Parliament, E. (2021). Plastic in the ocean: the facts, effects and new EU rules. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20181005STO15110/plastic-in-the-ocean-the-facts-effects-and-new-eu-rules

Pednekar, S., Some, S., Rivankar, K., & Thakore, R. (2022). Enabling factors for sustainable menstrual hygiene management practices: a rapid review. Discover Sustainability, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-022-00097-4

Scranton, A. (2013). Chem Fatale: Potential Health Effects of Toxic Chemicals in Feminine Care Products. https://womensvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Chem-Fatale-Report.pdf

Singh, J., Mumford, S. L., Pollack, A. Z., Schisterman, E. F., Weisskopf, M. G., Navas-Acien, A., & Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A. (2019). Tampon use, environmental chemicals and oxidative stress in the BioCycle study. Environmental Health, 18(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0452-z

UNEP. (2021). Single-use menstrual products and their alternatives: Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments. https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/UNEP-LCI-Single-use-vs-reusable-Menstrual-Products-Meta-study.pdf

UNICEF. (2019). GUIDE TO MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MATERIALS. https://www.unicef.org/media/91346/file/UNICEF-Guide-menstrual-hygiene-materials-2019.pdf

Upson, K., Shearston, J. A., & Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A. (2022). Menstrual Products as a Source of Environmental Chemical Exposure: A Review from the Epidemiologic Perspective. Curr Environ Health Rep, 9(1), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-022-00331-1

van Eijk, A. M., Jayasinghe, N., Zulaika, G., Mason, L., Sivakami, M., Unger, H. W., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2021). Exploring menstrual products: A systematic review and meta-analysis of reusable menstrual pads for public health internationally. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0257610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257610

Weir, C. S. (2015). In The Red: A private economic cost and qualitative analysis of environmental and health implications for five menstrual products Dalhousie University]. https://cdn.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/science/environmental-science-program/Honours%20Theses/2015/ThesisWeir.pdf

WoMena. (2019). What is the environmental impact of menstrual products? WoMena. https://womena.dk/what-is-the-environmental-impact-of-menstrual-products/