Addressing soil plastic pollution in the Nordic countries

Written by Cecilie Baann and Amy-Kristine Andersen, NIVA

See all the presentations from the webinar here.

Plastics is now likely the single most abundant anthropogenic substance found in soils. Studies show that the current environmentally relevant level of microplastic pollution in soils at the global level impacts plant physiology and soil microbial functions. Further, plastics contains a variety of chemicals, and its presence in soils may increase the bioavailability of toxins including heavy metals. Taken together, soil plastic pollution has the potential to impact both food security and food safety in the Nordics.

Agriculture in the Nordics is highly varied, with the climate ranging from temperate to arctic. Denmark has the most intensive agricultural production, with cultivated land making up 60 % of its landmass, whereas the other Nordic countries have a relatively small proportion of their land mass for agriculture. In 2020, the Nordic countries had 8 % of the EU total arable land. With regional conflicts and a tense international geopolitical scene affecting trade of food items, several Nordic countries are advocating for increasing national food production. This may lead to more use of agricultural plastic inputs in the Nordics, again resulting in higher potential for soil plastic pollution if measures are not taken.

Pilot soil microplastic monitoring show that Nordic countries have an on average lower level of microplastic contamination than southern European fields, but pollution hotspots have been already detected, with some agricultural fields in the Nordics presenting high levels of plastics. Of special concern in the Nordics is the incomplete degradation of biodegradable mulching film, which is increasingly used by vegetable farmers in the Nordics. This leads to soil microplastic and chemical buildup in vegetable fields, including lettuce fields. Studies show that especially lettuce is vulnerable for microplastic uptake through their porous roots, which may expose human consumers to microplastics.

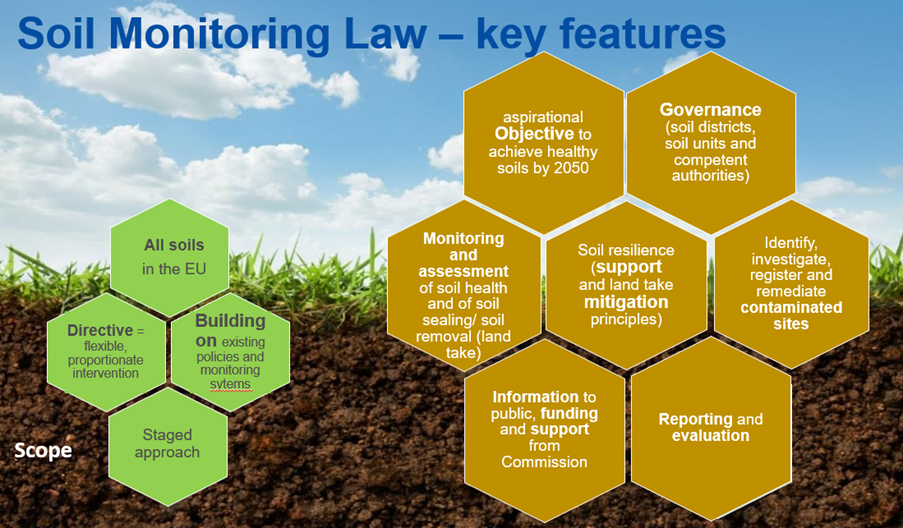

Figure 1: Overview of the key features of the EU Soil Monitoring Law, presented by Mirco Barbero

Scientific research findings presented at the recent Nordic AGRIFOODPLAST Network webinar held via IKHAPP on December 8th 2025, stress an urgent need for a precautionary approach that does not put food security or food safety at risk. In light of the recent approval of the EU Soil Monitoring Law, which will enter into force on December 16th 2025, we strongly encourage policy makers and authorities in the Nordic countries to establish soil monitoring programmes that include microplastics monitoring. Given the high level of imported food to the Nordics, we further urge policy makers in the Nordics to push for a high ambition within the EU and internationally for microplastics monitoring as part of a broader One Health agenda that interlocks human health with environmental, animal, soil, and plant health across the globe. Healthy soils in food-exporting countries can be essential to safeguard products quality and safety, and protect the health of people in the Nordics.

The use of agricultural plastics may increase in the Nordics in the coming years

FAO estimated in 2021 that there are 12,5 million tonnes of plastic used in agricultural production every year. In Finland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark combined, we estimate that a total of 58 000 tons of agricultural plastics used yearly on the farms for food production. These types of plastic are not covered by extended producer responsibility regulations on packaging waste. Instead, the countries have voluntary producer responsibility organisations that organise waste collection of agricultural plastics. Haybale silage wrap film is the agricultural plastic type most commonly used in the Nordics, and the waste management system works on average relatively well for this item. Nevertheless, because of the high volume used, silage wrap film is still the agricultural plastic item most commonly found polluting the environment.

Figure 2: Haybale silage wrap film can pollute the environment if not correctly managed

In the production of vegetables, berries, and fruits, a number of different plastic items are used in direct contact with soil, including mulching films and plastic fleece covers. The use of these plastic items is likely to increase in the light of the Nordic countries political priority of increasing food security and self-sufficiency. In other words, we estimate that as we increase the Nordic production of fruits and vegetables, we also increase the use of agricultural plastics. These plastic items are currently difficult and expensive to recycle. Furthermore, their use in direct contact with agricultural soil is a source of microplastic pollution to those same soils. Based on the data from the pilot soil microplastics monitoring conducted under the PAPILLONS project, agricultural plastic accounted for 18-40 % of microplastics found in European agricultural soils. While the soil samples in the project from Norway and Finland had on average less microplastics from all sources than the EU average, an increase in the application of agricultural plastics on Nordic agricultural fields is likely to increase the level of soil microplastic pollution in food producing soils.

Agricultural soils are recipients of microplastic pollution from many sources. Some of this pollution comes directly from agricultural plastics, whereas some comes from atmospheric deposition; airborne plastic pollution stemming from our modern lives and practices that involve plastics. Other sources that contribute directly to soil microplastic pollution are the application of sewage sludge, biogas digestate, compost, and polluted irrigation water. The microplastic content in these is again a result of our collective actions that leads to plastic fragmentation and buildup in residual raw materials – a lesser-known negative consequence of increasingly circularity. The answer is not to reduce circularity, but to target the sources that contribute to the highest level of microplastic pollution in soils. This can only be achieved through soil microplastic monitoring.

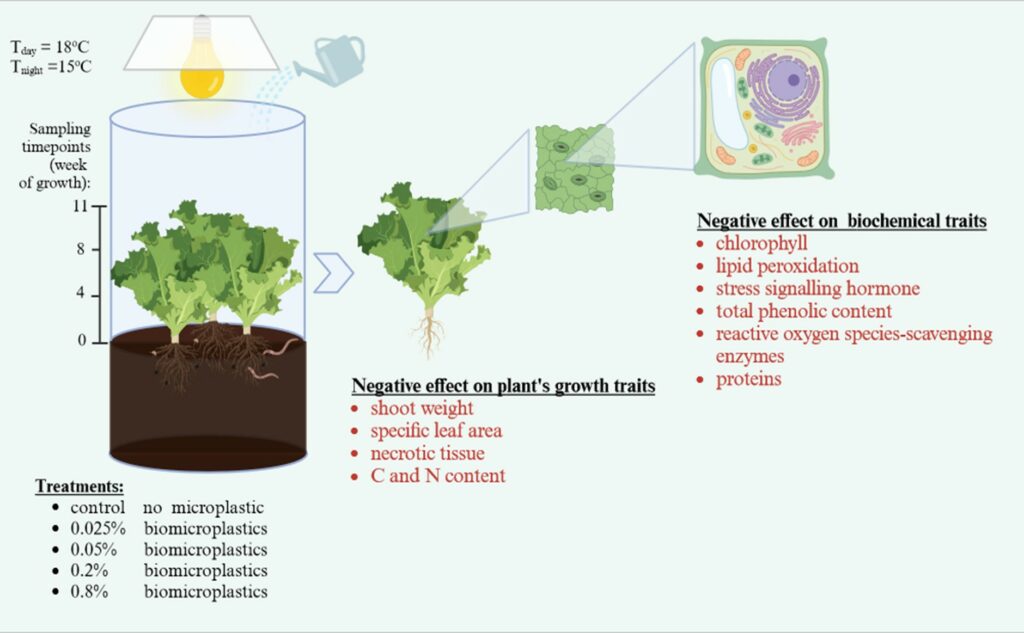

Soil microplastics have negative effects on plants

It has become increasingly common among vegetable farmers in the Nordics to use a biodegradable mulching film made of a starch-PBAT blend. This film is often called biofilm or maize-plastics among producers and local government officials. Many farmers have made the switch from conventional polyethylene mulch film to the biodegradable one, because of high labour costs involved in removing the conventional film, and because the biodegradable mulch film has been branded as a more sustainable and environmentally friendly option.

During the Nordic AGRIFOODPLAST Network webinar, scientist Rachel Hurley presented findings from the pilot monitoring study that shows incomplete degradation of the biodegradable plastics used on some fields in Finland. It is likely that the cold and wet climate in the Nordic countries have an impact on the rate of degradation of the film. Interviews in the research project PROLAND in Norway document how the biodegradable mulching film can be used by farmers up to three times per year on the same field. This high rate of application is likely to lead to the buildup of soil microplastics from the biodegradable mulching film.

Based on pot-plant experiments, senior scientist Sannakajsa Velmala presented research from the project PAPILLONS that found microplastics from both conventional LLDPE and biodegradable PBAT effected the early development of lettuce and carrot plants, with the biodegradable plastics having the strongest adverse effects. In particular, significant effects on important soil processes related to the recycling of nutrient and organic carbon were observed, while plants experienced a significant stress response when exposed to microplastics in both laboratory and field conditions, regardless of whether the plastic was biodegradable or not.

Figure 3: Figure representing lab experiments that imitate field conditions presented by Sannakajsa Velmala (LUKE)

Furthermore, lab experiments that imitate field conditions showed that biodegradable PBAT microplastics induced profound changes in lettuce defence mechanisms and to some extent deteriorated growth traits and nutritional attributes. Chief scientist Luca Nizzetto called these findings quite dramatic: “Based on these studies, and the recent literature review provided through the FAO report, we are talking about a real concern of microplastic pollution in soil, as we already measure plastic concentrations in soils across Europe at the levels research indicate as problematic. This presents serious challenges for soil health, for agriculture and food production, potentially also for our human health.”

The EU Soil Monitoring Law recommends monitoring soil microplastics

Based on his decade-long research on soil microplastic pollution, the PAPILLONS project team, with the support by researchers from other projects, had a direct policy dialogue with the European Commission in the months leading up to the adoption of the EU Soil Monitoring Law. The Soil Team at the Directorate-General for Environment, represented at the Nordic AGRIFOODPLAST Network webinar by its leader, Mirco Barbero, demonstrated attentiveness to the latest scientific research findings on soil microplastic pollution. The inclusion of microplastic as an emerging soil contaminant recommended for national soil monitoring adopted in the final stages of the EU Soil Monitoring Law development attests to official concern over the seriousness of microplastic pollution to soil health and resilience, this despite research in this area and key evidence emerged only very recently. While microplastic is not a mandatory component under the EU Soil Monitoring Law, Barbero adds that the law reflects the Commission’s position on micro- and nanoplastics as emerging contaminants that can pose a risk to soil health. Further, through the Joint Research Centre, the Commission is working to identify the best techniques for measuring microplastics and nanoplastics in soil and providing member states with a recommended methodology for conducting soil microplastic monitoring.

Figure 4: Leader of the Soil Team at DG Environment Mirco Barbero presenting the EU Soil Monitoring Law to the Nordic AGRIFOODPLAST Network participants

To ensure comparability, but also cost-effectiveness, it is advisable that the countries work towards a harmonized approach for soil microplastics analysis. Scientist Rachel Hurley highlights how there already is quite a lot of variation between different countries’ and institutions’ approaches. However, she emphasizes that timing now with EU Soil Monitoring Law recently adopted and to be transposed into national regulations within the next three years, provides an opportunity. “If the countries come together in agreement over what questions they would like to answer with data on soil microplastic pollution, we can identify a shared harmonized monitoring methodology that can be rolled out across Europe,” Hurley says. This approach will help reduce the costs of analysis and improve data comparability.

The rationale for a Nordic approach to the challenge of soil microplastic pollution

With increasing national food production in the Nordic countries, the use of agricultural plastics is likely to increase given current practices at farm level. While good practice examples exist in the Nordics, there are circularity challenges related to rising fractions of plastic items used. A substantial fraction of the agricultural plastic in use in the Nordics cannot be recycled, either because of costs, lack of infrastructure, or because the material is heavily contaminated by soil and chemical residues. The shift to biodegradable plastic alternatives currently does not represent a solution to soil microplastic or chemical pollution, as research indicates incomplete degradation of these materials in Nordic soils and climates.

With the current scientific knowledge on the impacts of soil plastic pollution, we urge the Nordic countries to take responsibility for our shared future food security, food safety, and interdependent One Health. Given the specificities of Nordic agriculture and climate, we cannot rely on other countries’ efforts to monitor microplastic levels in their agricultural soils. The Nordic countries have expressed strong international commitments to stopping plastic pollution to the environment. We have a long history of environmental monitoring successfully shaping targeted measures to reduce harm to the environment and human health. By implementing soil monitoring programmes that include microplastics, the Nordic countries can preempt long-term degradation of the invaluable agricultural soils in our region. By taking the lead in soil microplastic monitoring, the Nordics can be a lighthouse guiding example for other countries to follow, which on a local scale will ensure the food safety of our imported food produce, and on a global scale promote the safe and sustainable use of our shared planet and environmental resources.

Figure 5: NIVA researchers conducting soil sampling of Norwegian agricultural fields with plastic mulching film

References

- FAO Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: A call for action. 2021

- FAO State of research on the impacts of plastic pollution on soil health and crops 2025

- Adamczyk et.al. (2024) DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125307

- Zantis et.al. (2024) DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173265

- Directive (EU) 2025/2360 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 November 2025 on soil monitoring and resilience (Soil Monitoring Law)

- Nordic Statistics Database: nordicstatistics.org

- Nordic Council of Ministers TemaNord 2025:550: Changes to agricultural land use in the Nordic countries

- Forum Landbruksplast: forumlandbruksplast.no