Safeguarding our soils: A new priority in microplastic research

(photo by: Krystina Jarvis/Unsplash)

The potential impact of microplastics on our oceans has received a great deal of attention. Now, recent studies have begun to shift this focus: estimates suggest that soils could actually represent a larger reservoir for microplastic than the sea.

What does microplastic contamination mean for our soils?

Soil environments are one of the main environmental recipients of microplastic. Small plastic particles can form from the use and removal of plastics used in agriculture, as well as the application of sewage sludge to land – which contains the microplastics that are collected in wastewater treatment plants. Microplastics that enter soils can accumulate, with concentrations increasing over time, or can be washed into nearby streams and contaminate other environments. Yet, very little is known about soil microplastic contamination across the world.

Microplastics have the potential to disturb the functioning of soils, as well as the organisms living in them. Soils cover 71% of the global land surface and yet soil resilience is largely governed by processes that physically take place at the micrometre scale. Microplastics can interrupt the way in which soils form or how they retain moisture. Microplastics can also disturb soil organisms, altering their behaviour or impacting their health. Even though these processes often occur on a microscopic scale, they can have knock-on effects that could impact soil fertility, crop quality, and agricultural yields.

Residue of plastic film found in the soil on a farm in Norway (photo by Rachel Hurley)

We need healthy soils

The dirt beneath our feet is more important that you might think at first glance. Soils allow us to farm the food that we need to eat. They are a substantial store of carbon and they play a crucial role in the water cycle, helping to buffer floods after rain. They are the largest reservoir of biodiversity on the planet. And yet, many soil environments are under pressure and global soil degradation is one of the major environmental and societal challenges that we face in the 21st century.

Soils are able to take some stress, but there are limits. Soils are dynamic and complex systems made up of sediments, organic material, and a dense network of small organisms including insects, fungi, and bacteria. These systems are self-organising and when stress is first placed on one or more of the components of soil, they can regroup and resist the disturbance. However, if we push the system too far, the reorganisation of all the complex processes can shift soils into a new state – a state which may not support the same benefits that healthy soils have to offer. Early changes may be reversible but, once you exceed a tipping point, then these shifts can become irreversible.

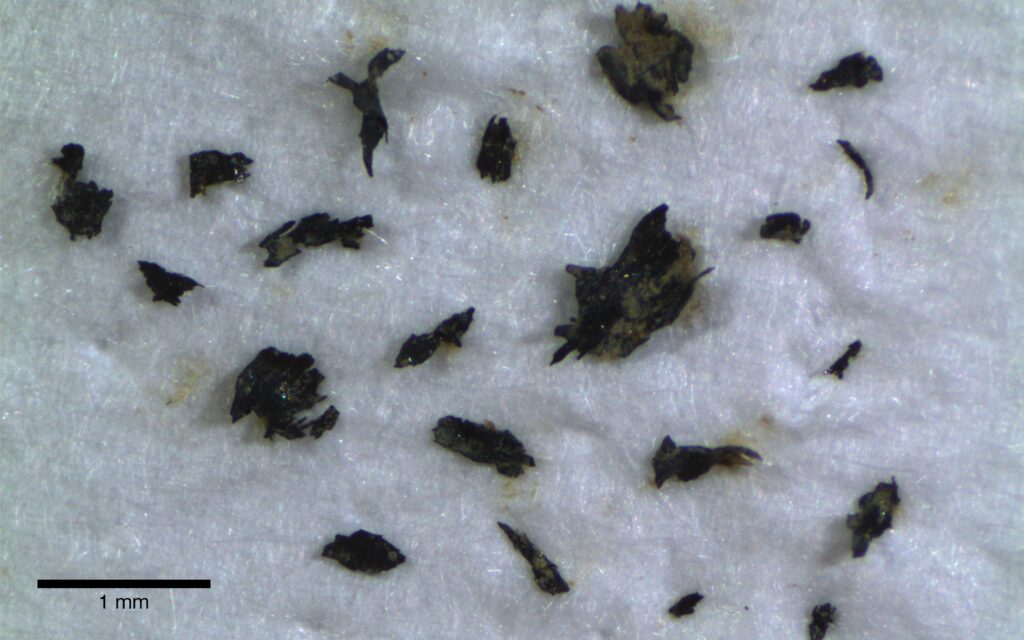

Microplastic particles extracted from a soil sample. These particles are tiny fragments of mulching film used in agricultural production (photo by Rachel Hurley).

The solution requires a holistic perspective

The solution might not be as simple as cutting out all inputs of microplastic to soils; microplastic pollution is not the only challenge that we face. Take global food security as an example. Soil degradation can threaten food security, and microplastic pollution may contribute to this. On the other hand, plastics used in agriculture – a source of microplastics to soils – can significantly increase agricultural yields by extending growing seasons and protecting crops from harsh conditions.

Right now, we don’t have a thorough understanding of the thresholds at which microplastic pollution will begin to stress soils and shift them into a different – and worse – state. We need to establish these limits and balance this against the need to ensure food production to feed our populations. This should take into consideration the potential for microplastics to accumulate in soils and reach high concentrations over time.

Agricultural plastics can be a source of microplastic particles to soils and the local environment (photo by Rachel Hurley).

Introducing the DIMISOR project

Using soil resilience as a lens for research gives us a way to take a long-term perspective. Biodiversity and soil functioning can be maintained and partially restored if we manage soils in a sustainable way. Assessments of the impacts of stressors, such as microplastic, on the resilience of soils are urgently needed to maintain and enhance the sustainability of global soil systems.

This is the core focus of the new project , funded by the Norwegian Research Council (2021-2024). The project will evaluate the impact of microplastics on the physical properties and microbial functioning of soils and identify thresholds and tipping points at concentrations which reflect present-day up to projected future contamination scenarios. This will give us crucial knowledge needed to safeguard the future sustainability of our soils.

| Written by Rachel Hurley, Research Scientist at Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA) |